Organic Mirin

Mirin has been part of Japanese cuisine for centuries. It was first consumed as a drink, like sake. Later, it came to be used as a seasoning, on discovery that this sweet rice wine could enhance the flavor of sauces and cooked dishes. Today, mirin is essential to any Japanese chef, whether cooking everyday dishes or haute cuisine. Mitoku supplies Mikawa Mirin, Japan’s finest traditional mirin, made from just three ingredients: glutinous rice, rice koji, and distilled rice spirit. It is produced by the Sumiya family using labor-intensive fermentation methods rooted in tradition. The result is a superbly versatile mirin that is particularly suited to sauces and stir-fried dishes, and also works well as a sweetener.

Mikawa Mirin’s Unrivalled Quality

More than one product is referred to as “mirin”, due to such factors as a historical shortage of rice. Broadly speaking there are three types of “mirin”. The first is mirin produced using traditional techniques, as exemplified by Mikawa Mirin. High-quality glutinous rice is used to make the mirin moromi (mash), which then undergoes a one year period of fermentation and maturation, during which time the starch turns slowly into sugar. The second is general mirin. Unlike traditionally produced mirin, the alcohol and water are added during a two to three month production period, and flavorings are added to round off the taste. Finally, there is a mirin-style condiment made by mixing chemical seasonings, liquid amino acids, and flavorings. This pale-colored seasoning is produced in just one day.

In 1910, when the current brewmaster Toshio Sumiya’s grandfather started the family shop, the production of mirin was a complex, exacting process requiring years of experience to master. After serving a long apprenticeship, Sumiya’s grandfather chose the perfect location to begin his own business, an area in central Japan known as Mikawa, where three great rivers flow into the Bay of Ise.

In 1910, when the current brewmaster Toshio Sumiya’s grandfather started the family shop, the production of mirin was a complex, exacting process requiring years of experience to master. After serving a long apprenticeship, Sumiya’s grandfather chose the perfect location to begin his own business, an area in central Japan known as Mikawa, where three great rivers flow into the Bay of Ise.

Now part of Aichi Prefecture, this region is known for its mild climate, high-quality rice, and excellent water. As a result of these ideal conditions, Sumiya’s grandfather was able to produce a mirin that was thick and rich beyond everyone’s expectations. It was named Mikawa Mirin, literally “three river mirin”, in honor of its birthplace.

The labor-intense fermentation methods still used by the Sumiya family are steeped in the history and culture of pre-industrial Japan. More than a process, the family’s work represents a way of life that, like Mikawa Mirin, is rare in the modern world.

At Sumiya Bunjiro Shoten, the year-long cycle begins in the fall with the making of koji, the 1,000-year-old fermentation catalyst, ubiquitous in Japanese cuisine, that kick-starts the fermentation of many important foods such as sake, rice vinegar, miso, shoyu, and tamari. The making of koji begins with one thousand pounds of locally grown rice, polished to remove the oily outer bran (preventing an off-taste), then soaked overnight in spring water. The following morning, the rice is steamed and then cooled until it is warm to the touch. Next, the producers sprinkle Aspergillus mold spores over the rice, mixing them in carefully so that each rice grain comes into contact with a microscopic spore. Finally, the warm inoculated rice is hurriedly carried to a uniquely constructed chamber called a muro. This traditional koji incubation room has three-foot-thick cedar-lined walls that are insulated with rice hulls.

Through the night, in the warm, humid conditions of the muro, the spores of the starter culture germinate, extending enzyme-laden filaments into each individual grain of rice. These filaments break down the complex carbohydrates, transforming them into sweet sugars. By morning, the 1,000-pound mound of rice is fused together into a dense, damp mass. Using their hands and wooden shovels, the Sumiyas work through the morning breaking up the huge mound of rice into individual grains. They work in temperatures of over 100°F with 100% humidity. While most visitors cannot stand the stifling air of the muro for more than a few minutes, the Sumiyas, after decades of acclimatization, work at a relaxed pace, stopping briefly to gossip or to wipe the perspiration from their faces. After lunch, the rice is placed in dozens of wooden trays and left to ferment for a second night.

Through the night, the Sumiyas visit the muro often to check on the developing koji and to regulate the muro temperature by opening or closing the windows, which are located in the ceiling. After decades of making koji, Brewmaster Sumiya notes, “It’s a world of mystery, which is better left to intuition than to modern technology.” Early the next morning, he enters the warm, misty muro to taste the fluffy-white, glistening koji. With a confident nod, he signals to indicate that the next phase of production can begin.

Although most mirin manufacturers, past and present, buy inexpensive shochu that has been distilled from molasses, the Sumiya family prepares its own from hand-made koji, premium rice, and spring water. These ingredients are mixed together and stirred each day for about a month. The resulting alcoholic mash, called sake moromi, is placed into cotton sacks, pressed, filtered, and distilled into clear rice shochu. This completes the first phase of authentic mirin processing.

Next, 2,000 pounds of sweet glutinous rice are soaked and steamed. Stripped to the waist, Sumiya’s youngest brother mounts a platform beside the rice steamer. Here he begins the backbreaking, hours-long task of shoveling the cooked sweet rice onto a cooling table. Before the day is over, he will repeat this process twice more, shoveling a total of three tons of rice. The cooked rice is then added to the shochu together with more koji. This second mash, called mirin moromi, is placed in 1,000-gallon enamel vats that are insulated with rice-straw mats. Apart from some occasional stirring, the mirin moromi is left alone to ferment for about three months. Gradually, the koji enzymes break down the complex carbohydrates and protein of the glutinous rice into sweet simple sugars and amino acids that blend with the shochu to form a delicious alcoholic rice pudding that, unfortunately, only traditional mirin manufacturers ever get to sample.

Standing over the huge vats, Sumiya sniffs the sweet rising vapors to judge the progress of the developing mash. A quick taste confirms what his nose has already discovered: It’s time to pump the mash into cotton sacks and press out its sweet essence. (The remaining flavorful pressed moromi is used to make delicious mirin pickles.) Finally, this sweet essence (immature mirin) is returned to the enamel vats and left to age for about 200 days. During the hot days of the long Aichi summer, the subtle color and flavor of the mirin develops further. In the fall, Sumiya and his brothers eagerly sample their 70,000-gallon golden harvest and confirm that grandfather’s recipe, unchanged after almost eighty years, yields mirin that is as delicious as ever. The mature mirin is then filtered through cotton and bottled, unpasteurized, for shipment to customers around the world. Continuing his grandfather’s commitment to quality while adapting to modern times, Sumiya now offers Organic Mikawa Mirin.

Mirin is often mixed with soy sauce to make other sauces, such as teriyaki. Mirin also goes well with miso and other fermented seasonings. It can also be added to stir-fries for extra flavor in the same way as white wine.

Mirin is often mixed with soy sauce to make other sauces, such as teriyaki. Mirin also goes well with miso and other fermented seasonings. It can also be added to stir-fries for extra flavor in the same way as white wine.

In addition, traditional mirin can be used in desserts such as cream caramel, fruit compote, and puddings. You can also make syrup sweetener with mirin by burning off the alcohol. While sucrose is the only sweetness component in sugar, mirin contains several sweetness components, including glucose, resulting in a greater depth of flavor.

Tips for using mirin in both western and asian cooking:

Sautéeing and Stir-Frying: Mirin adds depth of flavor to sautéed and stir-fried vegetable, fish, and noodle dishes. Its high natural sugar content allows it to burn easily, so it is often incorporated into a dish toward the end of cooking. This helps enhance and round out the flavors while contributing to the richness of the dish.

Simmering: Mirin is used to flavor many simmered and poached dishes including fish, shiitake mushrooms, reconstituted dried tofu, and deep-fried tofu. When simmering foods, use 1 tablespoon of mirin and 1 tablespoon of shoyu per cup of water or stock.

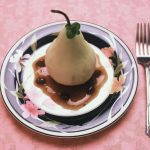

In Desserts: Mirin is a delicious addition to such desserts as poached pears, fruit cakes, tea cakes, and glazes.

In Dips: Dips for tempura and other deep-fried foods, such as mochi, almost always include mirin.

As a Liqueur: Here is where the value of mirin made with traditional ingredients and unhurried, natural aging is most obvious. While other mirins and mirin-like seasonings are unpleasant to drink, authentic mirin is delicious. Serve mirin chilled on ice or at room temperature, depending on the season. Enjoy it plain or with a little lime juice added. In Japan, mirin is sometimes served with ginger and hot water in the winter. It can also be combined with certain herbs to make a delicious medicinal tonic called o-toso.

In Marinades: Sake or other wines act as tenderizers and are preferred for marinating fish and poultry. Mirin, on the other hand, makes food more firm and helps it maintain its texture and shape. Mirin marinade is best used with such tender foods as tofu; however, it is occasionally added in small amounts to fresh fish in order to help tone down the strong taste and aroma.

In Noodle Broths: Mirin is the “secret” ingredient that lends a characteristic flavor to noodle broths and dips. Without mirin, these dishes tend to be flat.

In Sauces and Gravies: A tablespoon of mirin can transform a ho-hum sauce into a rich, gourmet delight.

In Sushi: Before sugar became cheap and widely available, mirin was used along with salt and rice vinegar to season sushi rice. Mirin makes the rice soft yet firm and gives the grain a desirable glossy appearance.

Related Recipes

-

Tofu in a Blanket

-

Nara-Style Tempura Dip Sauce (Vegetarian)

-

Somen on Ice

-

Clear Gravy

-

Noodles in Broth

-

Simmered Shiitake with Soy Sauce and Mirin

-

Zaru Udon

-

Poached Shrimp

-

Cider-Poached Pears

-

Sesame Ginger Miso Dressing

-

Teriyaki Tofu

-

Sushi Rice

-

Soy Milk Pudding

-

Tempura with Tempura Dip Sauce

-

Pecan Miso Dip

-

Tomato Sauce

-

Soy Sauce Flavored Pasta with Mushrooms

-

Teriyaki Grilled Seasonal Vegetables

-

Tomato Compote

-

Udon in Sesame-Miso Broth

-

Dried Daikon Pickles

-

Lotus Root with Carrot & Burdock

-

Shrimp Japonais

-

Arame with Lotus Root

-

Ginger Fried Rice

-

Shiitake Gravy

-

Hijiki with Dried Tofu and Vegetables

-

Arame with Fried Tofu

-

Summer Soba

-

Noodles with Miso Tahini Sauce

-

Japanese Style Fried Noodles

-

Glazed Acorn Squash

-

Green Beans Amandine

-

Burdock Kinpira

-

Squash “Pie” with Sweet and Savory Onion Topping

-

Mochi Soup (O-zoni)

-

Clear Soup

-

Dried Tofu with Ginger

-

New England Boiled Dinner

-

Marinated Steamed White Fish Fillets

-

Fat-Free Shiitake Sauce